By: Jose Gomez

When a former inmate first steps into the outside world, one of the challenges they may face is not knowing where to start over with their lives. With the challenges their criminal record imposes on them, it can become harder for former inmates to find jobs, seek treatment for mental health issues, access transportation, and restore their overall credibility as contributing members of society. These are some of the challenges that lead former inmates to offend again in a process called recidivism, which is the tendency of formerly incarcerated people to rely on criminal means again.

The issue of recidivism in the United States has become the defining factor of the country’s criminal justice system. Ideally, the people who directly influence recidivism rates—inmate educators, corrections directors, parole officers, etc.—should strive towards lowering it, since that would mean that former inmates would be less likely to offend again. However, the US is currently suffering a recidivism crisis, with more than 44 percent of former inmates being arrested just the first year after their release. [1] Despite decreasing percentages of former inmates who experience rearrest, around sixty percent of arrests occurred during the four to nine years after release.

A Brief History

To understand how we got to this point, we must trace back with a brief history of recidivism in the US. Ever since colonial times, punishment for criminal offenders has been rooted in dealing pain and despair as punitive justice. Punishments such as “floggings, mutilations, and hangings” with the inclusion of public humiliation were common in the era with little attention put to storing criminals away in cells. [2] In the years leading to the formation of the United States, there was a great shift towards the Quaker tradition of incarceration, then believed to be a more humane way of dealing with punishment. This shift then took the nation’s criminal justice system by its reins towards the end of the nineteenth century, re-shifting its focus towards building penitentiaries and systems akin to slavery for black Americans.

In response to the cruelties of the United States’ justice system at the time, many in the Progressive Era of the early twentieth century fought for reform. This movement eventually formed reformatories for people in prison likely to leave their criminal behaviors behind, with most of these being religious institutions. As the century progressed, major criminal justice movements allowed for the incorporation of the prison bill of rights that included the freedom of religion, cell cleanliness, personal advocacy, medical care, and being able to connect with the courts.

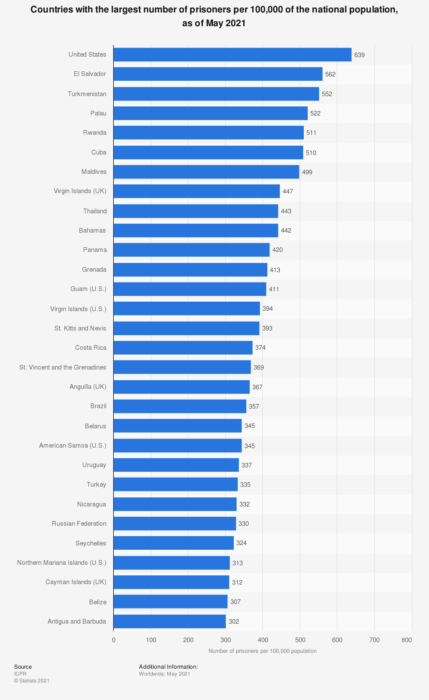

Though the criminal justice movements have come a long way since the punitive measures taken during colonial times, the US still has the largest prison population in the world. It was estimated in 2020 that there were approximately 2.12 million people incarcerated around the US, the highest number and percentage of any country and approximately 22 percent of the worldwide prison population—all despite the US being only 4.25 percent of the world population. [3] This comes as a result of Reagan’s War on Drugs in the 1980s and the adoption of mandatory sentencing by every state, which further increased the average time spent behind bars. With mandatory sentencing leaving little space for “substance use treatment, supportive services, and supervision,” which have been proven to reduce recidivism, there is an indirect relationship between the increase in mandatory sentencing in the War on Drugs era and the potential for an increase in recidivism, which did occur. [4]

As a result, recidivism rates skyrocketed to their proportions today, which further worsened the prison population crisis. It has been indicated that “the experience of prison does not provide a significant deterrent to those who have been imprisoned,” posing current prison norms as outdated and in need of educational, administrative, and restorative reforms. [4] The fact that prison itself does not undermine criminal behaviors suggests that prisons are not investing enough in programs to prepare people for the problems they will face in the outside world, leaving formerly incarcerated individuals questioning whether the state of being in prison is beneficial to them or not. And granted that around 95 percent of all incarcerated people in the United States will eventually be released from their sentences, recidivism is more than just a backend hiccup that can be taken of later with harsher prison sentences. What is done to influence recidivism rates will affect millions of people seeking to reintroduce themselves into society, including those who are left with no options other than crime to survive.

Moving Forward

So what can be done to reduce recidivism rates? Unfortunately, high recidivism rates are a multi-faceted problem that doesn’t have one clear solution. However, following the path of common trends among lawful former inmates can help us understand the areas in which our current justice system lacks the manpower and resources.

For example, in one study done in 2000, lower recidivism rates were found in groups of former inmates that were able to find employment following their release, even if it was marginal employment. [5] In another study by the US Department of Justice, inmates who went through “correctional education programs had 43 percent lower odds of returning to prison” in comparison to people in prisons who did not participate in such programs. Furthermore, this study indicated that “correctional education programs” are cost-effective and overall help former inmates get jobs; in addition, every one dollar invested into these programs brings back around “four to five dollars during the first three years after release,” indicating that these educational programs more than compensate for the costs imposed on struggling prison systems. [6]

Simply put, recidivism rates have skyrocketed to a point where it is essential for prison systems to act upon these reforms. The work Project Reclass does alongside all other prison education organizations, providing not only an education but also hope for those who only see a future as incarcerated peoples, is setting the example for the years to come. And though recidivism itself is a multi-faceted problem with no clear solution, it is up to us to be aware and provide for the great majority of people released from prison who are looking for a path forward that is both healthy and restorative.

[1] Alper, M., Durose, M., Markman, J. (2018). 2018 Update on Prisoner Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-up Period (2005-2014). (Report No. NCJ 250975). The Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/18upr9yfup0514.pdf

[2] Johnson, L. (2020, September 2). Recidivism: A Part of American History?. Medium. https://medium.com/dc-design/recidivism-a-part-of-american-history-f879be721b6

[3] ICPR. (2021, May). Countries with the largest number of prisoners per 100,000 of the national population, as of May 2021. [Incarceration rates in selected countries 2021]. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/262962/countries-with-the-most-prisoners-per-100-000-inhabitants/

[4] Pearl, B. (2018, June 27). Ending the War on Drugs: By the Numbers. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2018/06/27/452819/ending-war-drugs-numbers/

[5] Uggen, C. (2000, August). Work as a Turning Point in the Life Course of Criminals: A Duration Model of Age, Employment, and Recidivism. <i>American Sociological Review, 65(4), 529-546. doi:10.2307/2657381

[6] Department of Justice. (2013, August 22). Justice and Education Departments Announce New Research Showing [Press release]. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-and-education-departments-announce-new-research-showing-prison-education-reduces

The Author

José Gomez is an undergraduate at UChicago with an interest in economics and political science. Seeking a future career in immigration law, he is passionate about increasing awareness of migrants down at the border. José enjoys volunteering, running alongside Lake Michigan, and reading history books.